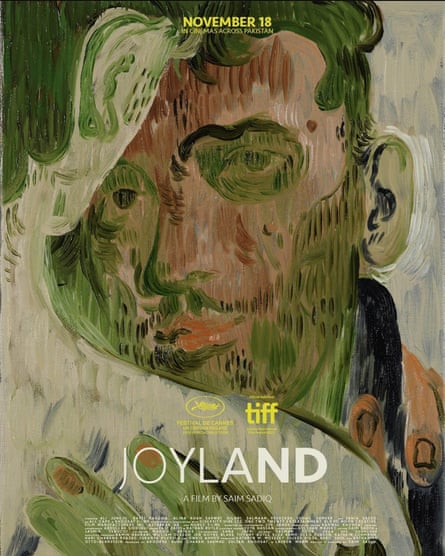

In August, Pakistan’s three censor boards cleared Saim Sadiq’s award-winning movie Joyland for launch. Shot in Lahore, the movie is a couple of younger married man from a conservative household who finds work at a dance theatre and falls in love with a trans lady struggling to land her second on stage. It was the primary Pakistani movie to display screen at Cannes and it received the Un Sure Regard prize, receiving a standing ovation practically 10 minutes lengthy.

Regardless that the movie was then topic to varied bans in Pakistan, after being accused of pushing an LGBTQ+ agenda and misrepresenting Pakistani tradition, it lastly appeared in Pakistani cinemas in November, with Malala Yousafzai signing on as govt producer.

No matter occurs at house, (the whiplash by no means appeared to finish, because the Punjab censor board reversed course as soon as extra and re-banned the movie) the movie’s subsequent journey shall be to the Academy Awards, as Pakistan’s submission for finest international movie.

This drama is nothing new. Pakistanis have all the time understood their heritage to be culturally wealthy and transgressive: from the romance of the Urdu language, spoken by poets and in royal courts, to qawwali singers as numerous as Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Abida Parveen, to tv dramas and literature. Artists resembling Iqbal Bano sang songs in opposition to dictators and exhibits on state tv satirized army juntas with jokes so subtle that even military censors couldn’t catch them. In 1969, Pakistan state tv aired Khuda Ki Basti, or God’s Personal Land, a collection set in a Karachi slum within the tumultuous days after independence, from a basic Urdu novel. To make sure that the drama was devoted to the novel, Pakistan state tv convened a board of intellectuals to supervise the scripts, together with Faiz Ahmed Faiz, one of many nation’s most beloved poets.

Right now, Pakistani artists are garnering worldwide consideration as they proceed this legacy of confronting themselves and their society, interrogating faith, sexuality and sophistication hierarchies.

“Folks say, ‘Oh, they’re telling poor individuals’s and underdog tales,’” says Sarmad Khoosat, “however that’s the place the reality is, I really feel.” Khoosat, who produced Joyland and whose manufacturing home Khoosat Movies is on the helm of Pakistan’s cinema renaissance, made an enormous splash when his movie Zindagi Tamasha was banned in 2021. Moreover the Khoosat-produced movies, The Legend of Maula Jatt, a remake of a 1979 movie, introduced in $10m (£8m) on the field workplace and Sandstorm, a brief directed by the London-based film-maker Seemab Gul, initially from Karachi, was nominated for finest brief movie on the Venice movie pageant and has garnered loads of Oscar buzz. Pakistan can also be the setting of Jemima Khan’s debut movie as scriptwriter, What’s Love Obtained to Do With It?, starring Emma Thompson and premiering within the UK in February.

Individuals who assume the edgy subject material is meant for international audiences don’t perceive Pakistan, Khoosat says. “They don’t realise that faith and trans individuals and socioeconomic divides are realities right here. They’re our tales.”

Sadiq advised the Guardian he strongly disagreed with the marketing campaign in opposition to his movie. “I feel it’s as empathetic a portrait of Pakistanis as you’ve ever seen on display screen,” he stated. “It’s truly a very empathetic portrait of conservative Pakistanis.” And the supposed promotion of a sinister LGBTQ+ agenda, Sadiq stated was “frankly, for my part, bullshit”.

Trans individuals, often called khwaja sira, held positions of energy within the Mughal courtroom and weren’t simply thought-about devoted guards and protectors but in addition bestowed with ceremonial significance. At Cannes, the director and his producers had a surreal second watching a packed theatre of over a thousand individuals cheering and clapping when Alina Khan, who performs Biba, lastly takes the stage for her huge tune and dance quantity. When the credit rolled, Sadiq discovered himself crying and turned to Khoosat solely to see him in tears too. The editor was crying, the actors, the crew, the viewers.

Artwork versus commerce

Pakistan by no means had the cash or equipment to supply artwork at scale as its neighbour, India, was capable of do with Bollywood. And that is maybe why it has taken the world so lengthy to get up to Pakistani tradition.

The distinction is considered one of artwork versus commerce. Although commercially unable to compete with Bollywood, Pakistani movies, tv and music are arguably extra subtle and daring. Although Bollywood movies from earlier a long time addressed injustice, feudalism and political oppression, immediately the trade is little greater than a mouthpiece for India’s quasi-fascist rightwing authorities, obsessive about spit-shining the picture of its prime minister, Narendra Modi. Current movies resembling Swachh Bharat, or Clear Up India – based mostly on a program which, so far as anybody can inform, is about cleansing all the nation, one hand-held broom at a time – or Sui Dhaaga, Needle and Thread, whose tagline is “Made in India” and which relies on one other self-explanatory initiative – have been little greater than authorities puff items. Once they have run out of Modi initiatives to construct total movies round, Bollywood producers flip their eyes to army operations the place motion heroes with greased, rippling eight packs, based mostly on modern-day and revisionist historic figures, wipe out Muslims on the battlefield.

With out having to fulfill paranoid governments, enhance field workplace receipts or please audiences of a billion individuals, Pakistani artists have been capable of take extra dangers with their work. The nation’s flip in the direction of conservatism is pretty latest, a results of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s CIA-backed fundamentalist dictatorship, which ravaged the nation between 1977 and 1989, however even then, within the darkest days of army rule, artwork thrived despite and in resistance to the junta.

On the seventy fifth anniversary of independence this August, Indian residents have been instructed to hoist their tricolour flag from their houses by Modi, and social media was replete with well-known Indians, together with Shah Rukh Khan, waving and posing in entrance of their flag whereas saying how good it was to reside on the earth’s largest democracy. One struggles to think about Pakistanis, who’ve lived underneath authoritarian regimes for a lot of our historical past, acquiescing to such ominous dictates so politely or enthusiastically.

In any case, it was underneath Pervez Musharaff’s dictatorship that the Booker-longlisted writer Mohammed Hanif revealed his debut novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes, about one other Pakistani dictator’s airplane being blown up mid-air. Although Pakistan by no means stopped producing tradition – not throughout any of our 4 coups, nor throughout bloody durations of inner and exterior strife – immediately a wave of progressive and provocative work is lastly getting recognition far past the nation’s borders.

Music and visible artwork

All this excellent news is uncommon however welcome now greater than ever, after Pakistan was devastated by a super-flood this 12 months that displaced 50 million individuals, worn out staple crops and produced a well being and starvation disaster that continues to unfold.

“We’ve been having a very onerous time in a post-9/11 world,” says the Brooklyn-based Arooj Aftab, the primary Pakistani musician to win a Grammy, taking house the 2022 award for finest international music efficiency. Aftab’s album Vulture Prince reimagines conventional ghazals, melancholic love poems born out of Arabic and Persian literary traditions. “There’s been a major quantity of Islamophobia and loads of dangerous advertising and marketing in the direction of Pakistan on the whole – associations with terrorism and ache and Afghanistan-adjacent confusion – whereas the narrative round loads of different south Asian international locations is like ‘Oh my God! Magnificence! Unique landscapes! Yoga!’ And the west loves that shit.”

Whether or not exhausted by orientalist tropes about south Asia, tragedy porn or the low-thrumming racism that marked the Trump years, immediately the west appears to be embracing non-English tradition at tempo. Pasoori, Ali Sethi and Shae Gil’s breakout tune about difficult love, drawn from the separation of India and Pakistan, is the primary Pakistani tune to prime Spotify’s international viral chart and was essentially the most Googled tune of 2022, beating out international behemoths resembling BTS. The tune, whose Punjabi title means “issue”, has had over 440m views on YouTube and is essentially the most profitable tune to come back out of Pakistan’s famed music incubator and TV present Coke Studios, which has introduced modern singers along with conventional musicians to large acclaim since 2008.

Boiler Room, a London-based on-line radio station, broadcast a Pakistan particular this summer time streaming singers, DJs and even conventional Baloch musicians to their on-line audiences. “The ceiling is being utterly shattered,” Natasha Noorani, considered one of Boiler Room’s featured artists, stated. And that shattering reverberates as a result of Pakistani musicians are “exploring their identities in a means that isn’t whitewashed or pandering to some sort of international attain the place you might be advised to sing in English or do a fusion or costume English”.

Earlier than something goes international, Noorani believes, it has to ring a bell at house. Musicians locked down throughout Covid waves have been creating albums of their bedrooms, on their telephones and laptops, and in doing so have “dismantled the equipment, the identical infrastructure that saved up the monopolistic tendencies of music”.

Prior to now few months, the modern Pakistani artists Shahzia Sikander and Salman Toor have been glowingly profiled within the New Yorker; Toor’s 4 Buddies just lately offered at a Sotheby’s public sale for $1.2m (£0.99m). His work are celebrated for his or her depictions of queer intimacy, and reimaginings of classical masterpieces from Caravaggio to Édouard Manet. “My speedy response was that this artist may paint something and make me consider in it,” wrote the New Yorker’s Calvin Tomkins.

TV celebrates the diaspora

In the meantime, Pakistani diaspora tv is having a celebratory second. Exhibits by creators of Pakistani origin resembling Bilal Baig are radical and refreshingly difficult. HBO Max’s Type Of (tagline: “the long run is theirs”) is the story of Sabi Mehboob, a gender-fluid Pakistani Canadian working as a nanny for a household in disaster whilst they attempt to maintain their very own crumbling life collectively. The present is wry and intelligent, subverting all the usual tropes about south Asian households. Sabi’s sister, Aqsa, protects them whereas managing her personal messy romantic life and their mom struggles extra with understanding why they’d be a nanny – “like Mary Poppins? You’re telling me you’re a servant?” – than with their sexuality.

Class and hierarchy, within the subcontinental creativeness, has all the time been extra fraught than intercourse. Earlier than the prudish intervention of the British, who ordered and organised Indian life into slim bins, the south Asian method to sexuality was all the time fluid, a heritage that Type Of, Joyland and even Khoosat’s Zindagi Tamasha have all embraced. Although Type Of has been renewed for a second season, premiering on HBO in October, maybe extra well-known is Ms Marvel, showcasing the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s (MCU) first Muslim and Pakistani diaspora superhero.

Ms Marvel follows Kamala Khan, whose mother and father, previously of Karachi and now of New Jersey, aren’t caricatures of immigrant mother and father, however droll and charming, embarrassing in the way in which all mother and father are whereas their younger daughter suffers the indignities of youngsters all over the place. The writing group is aware of solely too effectively the codes and ciphers of Pakistani life and have seamlessly blended them into this Disney story. Kamala has a brother who prays always (each Pakistani household has one resident fundamentalist), her father quotes poetry on the dinner desk and Nakia, her hijab-wearing finest pal, has her footwear stolen on the mosque – a timeless ceremony of passage for all mosque-going Muslims.

The group behind Ms Marvel consists of a few of Pakistan’s smartest creatives: from the administrators, together with the two-time Oscar winner Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, to the music provided by Coke Studios, to the actors, together with the revered theatre actor Nimra Bucha and heartthrob Fawad Khan.

Although Ms Marvel quick grew to become the best-reviewed present within the MCU canon, preliminary studies have proven that it has a considerably decrease viewership than different Marvel blockbusters, pulling in lower than half the viewers that WandaVision introduced in in its first week. Critics have kindly supposed that the numbers are to do with Ms Marvel being a brand new character and the actors being comparatively unknown stateside, however in a rustic whose political discourse has been blisteringly Islamophobic during the last 20 years, a Pakistani-origin Muslim as a superhero could also be an excessive amount of for conventional audiences. Although I cheered the present as a lot as each TV-watching Pakistani, it did give me pause that Kamala’s hero in Ms Marvel is Captain Marvel, an ex-elite fighter pilot within the US air power, the very division of the US army that flies the MQ1 Predator and MQ9 Reaper drones which have terrorised Afghanistan and Pakistan since 9/11.

‘I’m going to offer you this stunning factor’

Gone are the dire years of apologia and contrition as Pakistani artists journey worldwide.

“We’ve been actually sick of the stuff the place it’s like, ‘Are you able to please rating this actually extraordinarily unhappy documentary about Pakistan?’” Aftab says. “And I’m identical to, completely not. I’m not going to do this. White individuals like to witness and be moved by Black and brown tragedy. They don’t know find out how to see us completely satisfied and that’s actually deep and fucked up. It’s not fascinating for them to see us experiencing pleasure. As somebody who works in artwork, in music, it’s my duty to say, ‘I’m not going to offer you that. I’m going to offer you this different actually stunning factor that’s jazz and I’m going to make one thing that’s undeniably stunning and can transfer you and I’m going to be dedicated to that since you guys are so annoying.’”